Environment Visibility Is the Riskiest Assumption We Make

There’s a moment most senior technology leaders eventually experience, and it rarely happens during an outage. It happens in a meeting, sometimes with the board, sometimes in a customer QBR, sometimes with audit or compliance. Someone asks a question that sounds simple: what systems are involved, what’s connected to what, and where does the risk actually live?

You answer with confidence because you’ve earned it. You’ve invested in cloud controls, monitoring, access management, change processes, and governance. You have diagrams, ownership models, and an inventory.

But there’s often a quieter second layer under the answer: you’re assuming your environment visibility is as complete and current as you need it to be.

By environment visibility, I mean this: can you see what’s running, how it connects, and what depends on what, in a way that matches today’s reality, not last quarter’s diagram?

That assumption is one of the riskiest ones we make, not because teams are careless, but because modern systems change faster than documentation can keep up.

The confidence gap leaders don’t talk about

Most organizations are not guessing. They are working with the best information they have. The problem is that even strong teams can be operating on a picture that is slightly out of date.

That is how surprises happen. A vendor integration becomes essential over time. A “temporary” workaround sticks around. A shared service quietly becomes a dependency for many other systems. These are hidden dependencies, and they often stay hidden until something breaks.

Why modern environments can’t stay “understood”

Environments drift in small ways every week. Services get added. DNS records change. Network routes shift. Teams introduce quick fixes to solve real problems, and those fixes sometimes become permanent.

On paper, everything looks accounted for. In practice, you are running a living system. Static documentation struggles in living systems because it captures a moment, not ongoing change.

That is why painful postmortems often include a line like: we didn’t realize that depended on this. In modern systems, risk is not only what you run. It is also your system dependencies, including the ones you did not know were load-bearing.

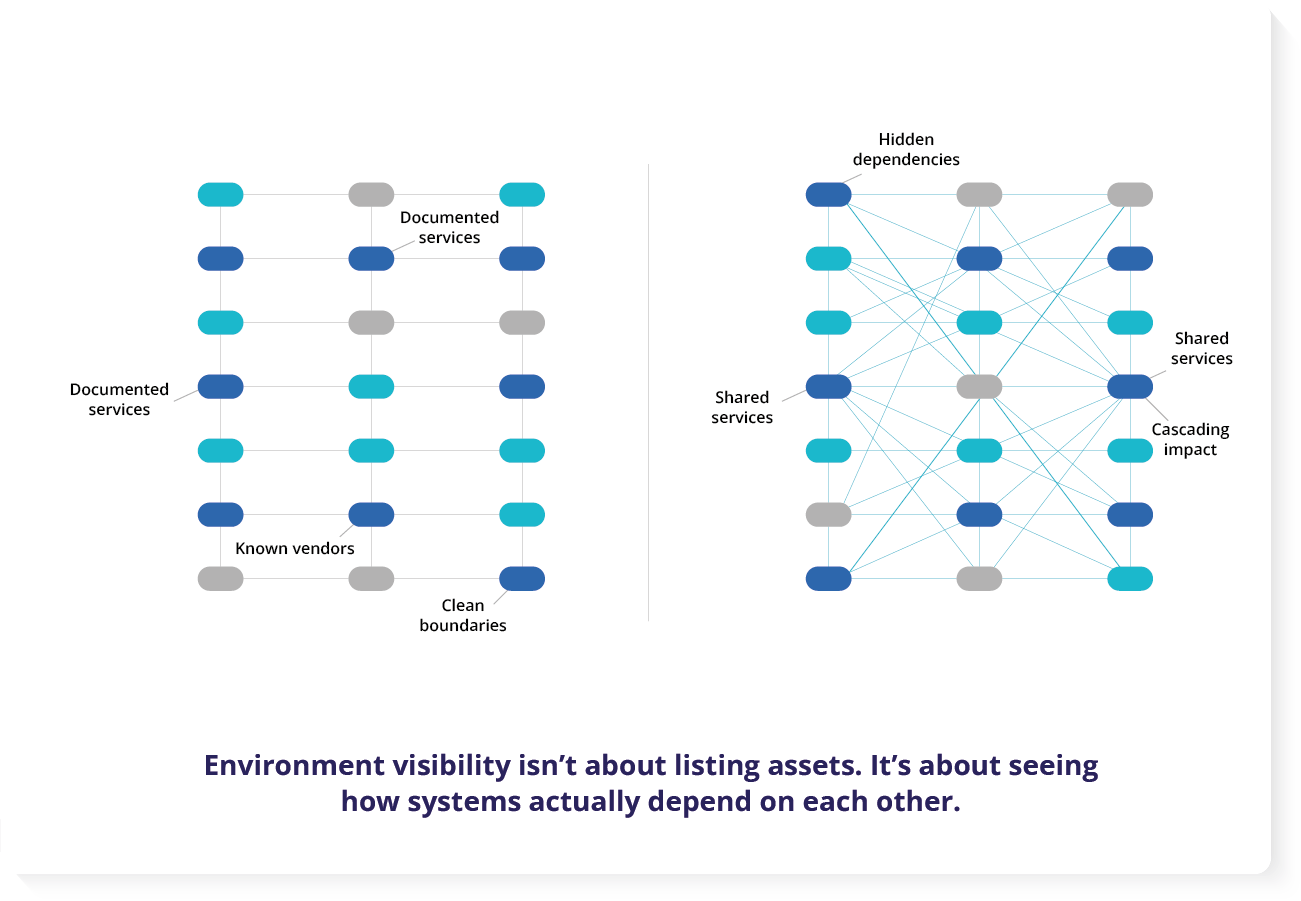

Inventory tells you what exists. Impact tells you what matters.

A lot of teams still treat inventory like a list, a CMDB record, a spreadsheet, or a periodic scan that dumps assets into a database. That approach made sense when the main goal was “know what exists.”

But leaders usually need different answers:

- If this asset degrades, what breaks?

- If this provider is impaired, who feels it first?

- If this route changes, what becomes unreliable?

Those are impact questions. They require dependency visibility and simple impact analysis, based on current relationships, not assumptions.

What follows is a simple picture of the difference between an environment that looks understood and one that’s actually operating.

Environment visibility is not documentation

In late 2025, Forrester made the case that traditional CMDB thinking struggles when systems move too fast for static records. The useful takeaway is not “throw it away.” It is this: a database of entries is not the same as understanding how your environment behaves today.

You can have a complete inventory and still be surprised because the inventory does not explain relationships well enough. And when relationships drift, environment visibility becomes something you hope you have, instead of something you can rely on.

A 2025 report on EPA oversight also pointed to a familiar issue: incomplete or inaccurate inventories of systems and software assets. That is not unique to one agency. It shows how hard it is to keep system understanding current when the environment keeps changing.

When dependencies reveal themselves under stress

Most teams do not realize they are operating on assumptions until an incident forces discovery. Stress makes the real system visible.

You can see this pattern in public outage write-ups. Cloudflare’s June 12, 2025 outage post-mortem explained how a failure in Workers KV affected many customers because that component supported multiple Cloudflare products. The key point was not “storage went down.” The key point was that a shared dependency sat underneath many user-facing services.

ThousandEyes has also described in its outage analysis how cloud disruptions can trigger cascading failures across dependent systems, and that effects can continue even after the core issue is fixed. Those aftershocks are what leadership fears, especially when customers are watching and teams cannot quickly scope blast radius.

This is where confidence gets tested. Not when everything is steady, but when the system is under pressure.

Reducing surprise is a leadership capability

Regulators are pushing leaders toward this reality, too. The SEC’s cybersecurity disclosure rules compress timelines and increase the need for clear, credible impact statements. If something may be material, leadership needs to explain what happened and what was impacted, quickly and accurately.

That is hard to do when your “source of truth” is a stale diagram and a patchy inventory.

So what do the best-run organizations do differently?

They treat environment understanding as something that must stay current. They invest in ways to keep relationships updated and queryable, so they can answer impact questions without guessing. This is where dependency mapping becomes practical, not academic.

That is where WanAware fits. It is built to maintain a living view of assets and relationships, so environment visibility is grounded in what is true now. When incidents cascade through hidden coupling, that can be the difference between reacting slowly and responding with confidence.

The payoff is simple: fewer surprises.

A lot of operational pain today isn’t caused by lack of effort. It comes from uncertainty. Teams cannot prioritize cleanly because they cannot see impact. Leaders hesitate on changes because they cannot gauge risk. Organizations overbuild redundancy because they are not sure where fragility lives.

When you strengthen environment visibility, you improve decision-making. And for leaders, that often matters even more than the tooling itself.

The hardest risks to manage aren’t the ones you can’t see. They’re the ones you assume you already understand.

In environments that change as quickly as ours do, reducing surprise starts with recognizing that assumption, and deciding not to operate on it anymore.